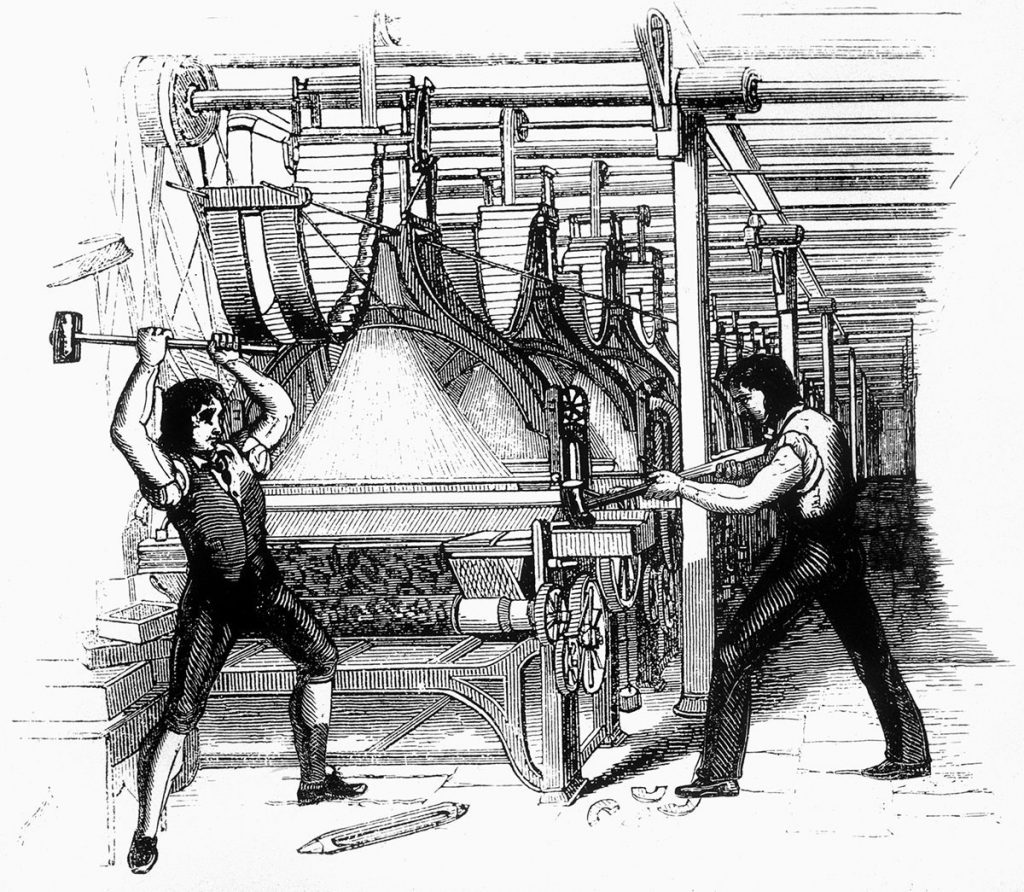

Luddites breaking down the door of a textile factory in England defended by its owners and troops Between 1811-1816. Engraving with modern watercolor.

In my last post, I mentioned the possibility of AI replacing humans in writing. I am pleasantly surprised at the post’s reactions, as they generated some great comments. So, I thought I’d clarify today what my own feelings on the matter are, something I only did summarily in the last post.

As someone who has worked with computers all my life, I don’t see AI replacing humans in creative endeavors. They will be used as virtual assistants, and their use will be as intuitive and unobtrusive as Siri or Googling something is today.

So, I find fears of AI rising to become humanity’s overlords overblown, to say the least.

No Overlords. But Still…

However, while I don’t fear AI, I do worry about people. Specifically, I’m worried about the pressure put on society because of robots and AI replacing workers, especially low-paid ones. Farmers, truckers, factory workers… all these people, along with many others, are in real danger of losing their jobs.

Yes, economists warn against the so-called Luddite fallacy: technological advances don’t inevitably generate structural unemployment. And they always create an increase in aggregate labor inputs.

However, there is a snag: that little word, aggregate. It means that the displaced worker’s children will probably find a good job as robot technicians or what. But what about the replaced workers? Many of them will be too old or unwilling to switch careers. This creates a lost generation. And plants the seeds for societal upheaval.

The Industrial Revolution and Luddites

In all this, I see strong parallels with the Industrial Revolution and the rise of the Luddites (not to be confused with the Ludites or Ludim, the Hebrew term for a people mentioned in Jeremiah and Ezekiel).

As Wikipedia explains, the Luddites were a secret oath-based organization of English textile workers in the 19th century, a radical faction that destroyed textile machinery as a form of protest.

Luddites feared that the time spent learning the skills of their craft would go to waste, as machines would replace their role in the industry. Sound familiar?

The Luddite movement began in England, the hotbed of the Industrial Revolution, and culminated in a region-wide rebellion that lasted from 1811 to 1816. Mill and factory owners took to shooting protesters and eventually the movement was suppressed with legal and military force.

While historians suggest that the movements of the early 19th century should be viewed in the context of the hardships suffered by the working class during the Napoleonic Wars, rather than as an absolute aversion to machinery, it was the mass loss of industrial jobs that triggered the rebellion.

This theory is strengthened by the fact that a few years later, in 1830, an agricultural variant of Luddism occurred during the widespread Swing Riots in southern and eastern England, centering on breaking threshing machines.

Also, much earlier, handloom weavers burned mills and pieces of factory machinery and textile workers destroyed industrial equipment during the late 18th century, prompting acts such as the Protection of Stocking Frames, etc. Act of 1788.

To Understand the Future, Study the Past

Later interpretation of machine breaking (1812), showing two men superimposed on an 1844 engraving from the Penny magazine which shows a post 1820s Jacquard loom. Original unknown, this version from Learn History.

There does not seem to have been any political motivation behind the Luddite riots and there was no national organization. The men were simply attacking what they saw as the reason for the decline in their livelihoods.

Even so, they were a major disruption force in society. Luddites battled the British Army at Burton’s Mill in Middleton and at Westhoughton Mill, both in Lancashire. The Luddites and their supporters anonymously sent death threats to, and possibly attacked, magistrates and food merchants. Activists smashed Heathcote’s lacemaking machine in Loughborough in 1816.

Even without a leader, the Luddites were an important threat. The British Army clashed with the Luddites on several occasions. At one time there were more British soldiers fighting the Luddites than there were fighting Napoleon on the Iberian Peninsula. Can you imagine if a populist politician had taken their cause to promote their own interests?

This is the situation we will face in the near future, I’m afraid. Given the power of social media to help international social movements organize, I wouldn’t be surprised if I saw the wee one’s generation having to deal with Neo-Luddite uprisings.

The Aftermath

When three Luddites ambushed and assassinated a mill owner, and a Luddite group attacked a mill, the British government decided enough is enough. The government charged over 60 men with various crimes in connection with Luddite activities. These trials were certainly intended to act as show trials to deter other Luddites from continuing their activities.

While thirty men were acquitted, the harsh sentences of those found guilty, which included execution and penal transportation, quickly ended the movement. Parliament made “machine breaking” (i.e. industrial sabotage) a capital crime with the Frame Breaking Act of 1812.

So, things to look forward to in the next 30-odd years:

- Uprisings against robots and industrialists

- Legislation making such attacks illegal

- Politicians squabbling over the best way to deal with the issue

A Possible Solution

In antiquity, the abundance of slaves meant that people had free time to work on philosophy or conquest.

A similar solution may be on the horizon. An idea that has been gaining ground is that of a guaranteed minimum income. Essentially, part of the profits from introducing robots to the workplace is used to fund the workers replaced by robots. This may be the best way to solve the problem before it erupts into social anarchy.

Of course, even if this idea is widely employed, it ignores the fact that people take pride in their work. Small farmers who have spent generations toiling the land may hate the idea of robot-employing mage-farms gobbling them up and leaving them with a government stipend. Even though not in danger of dying of hunger, they may well resent the innovations that led them there.

It remains to be seen whether politicians, now and future, have what it takes to guarantee a peaceful outcome to this challenge. Those on the left will probably try to implement a mix of helpful solutions (like the guaranteed minimum income one) and unhelpful ones (like training farmers as computer programmers). Those on the right will probably prefer draconian measures against anyone threatening social order and stability.

Speaking of politicians, Lord Byron opposed the Frame Breaking Act of 1812, becoming one of the few prominent defenders of the Luddites. Indeed, he passionately denounced what he considered to be the plight of the working class, the government’s inane policies, and ruthless repression in the House of Lords in 1812:

I have been in some of the most oppressed provinces of Turkey; but never, under the most despotic of infidel governments, did I behold such squalid wretchedness as I have seen since my return, in the very heart of a Christian country.

Ironically, Lord Byron’s only legitimate daughter Ada Lovelace would become the first computer programmer by combining the technology of the Analytical Engine with the Jacquard loom.

However, if any of you write near-future science fiction, be sure to avoid adding such an ironic detail to your story: your readers would probably think it too far-fetched!

I find your article refreshing to read. Our evolution is evolving today at a much faster pace then it has in the past and that ‘in part’ is coming about as new things are discovered i.e. computers. As our information age takes root, I see a kind of restlessness going along with it, like a child that has a new toy and doesn’t really know what to do with it quite yet. It is still young but growing.

My intuition tells me that we, hopefully, should proceed with an air of caution and explore all avenues as we grow with it, as we all know many mistakes will happen along the way.

Always be open to those mistakes and be willing to learn from them.

Thanks so much for your historical insights.

Thank you so much for the kind words, Lynne! You’re right; computers and AI are still at their infancy. It remains to be seen what we do with them.

An insightful, thought provoking post. Sustainable changes are always welcome. The problem with today’s society is that it’s extremely profit oriented; destroying the world for short term acquisitions.

You hit the nail on the head. I do wonder if it’s ever been any different, mind you 🙂

I must say the older one becomes the more of a Luddite one becomes. As someone who is of the generation that used ink pens when at school I am definitely a Luddite where computers are concerned which prompted me to blog on a recent email I received about a computer problem which might as well have been written in Japanese, I have no idea why computer people can’t write in simple English.

Lol–that’s why I can make a living, Joe. By writing in plain English about hard (often technical) matters 😀

Thanks for the history and thoughtful insight. This conflict has been intensifying and is at the forefront of unrest in Seattle right now. This morning on the news they were discussing how all the tech companies, like Microsoft and Amazon, bringing in high end jobs/wages and driving up the cost of housing and commodities has displaced so many workers and families.

We have a homeless crises, crime is on the rise in the heart of our downtown shopping/business districts. Food banks are running out of food and giving to a section of the population they’ve never seen in need before.

About a year ago, the mayor was removed from office, and the new mayor approved a tax that required local corporations to pay a fee for every worker they employed that made over a certain annual salary. The funds were to be used to catch up on infrastructure that the mass influx of tech folks strained and specifically to build lower income level ‘affordable’ housing.

Most of us who have lived here prior to the tech boom were celebrating this unbelievable and sensible solution.

The new mayor repealed it in about a week to 10 days after enormous pressure from the businesses (and who knows what other behind the scenes reasons.)

Average citizens, and indeed the tech workers that live in the city, are currently picketing and swarming city hall after recent shootings (which are increasing quickly in number and severity) and demanding that our streets are made safer.

Boredom/joblessness of the laborers and homelessness are the problem. We are already facing hunger and violence due to these issues. The city I lived in for 23 years has changed from clean, beautiful and friendly to dirty, frightening and hostile.

I do think it starts with corporations giving back profits directly to help cities have resources to keep up with changes. But in the long run, people need occupations and meaning, not just homes and food, to be well.

Wow, thank you so much for sharing this, Sheri! I’d love to share your experience in the original post, too.

An interesting parallel I’ve often thought of myself. Modern day Luddites rail against the change from fossil based fuel to protect their jobs in the energy sector, but the movement is also anti-intellectual, and anti-science coupled with a resurgence of fundamentalist religions and populist demagogues. For some people, it’s much easier to believe than exercise their faculty for rational thought.

Agreed. That is why I don’t really Neo-Luddites as an offspring of the original ones. Rather, it feels they appropriated the name to lend their movement an air of legitimacy.

Another great post! A useful historical comparison too and you’ve highlighted some interesting facts that were unknown to me, so, thank you!

That is so kind of you, thank you!

Very interesting, NIcholas. Did you know there is a modern luddite movement called Neo-Luddism. Here is the wikipedia link if you are interested: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neo-Luddism. I don’t believe you can stop progress and we are going to have a lost generation. There are many articles on the World Economic Forum website that support this view. A lost generation and plans for greater social support for them. Of course, this doesn’t address the depression and social issues that arise outside of merely living.

Thank you, Roberta! I do know of Neo-Luddism. I feel they don’t really have much in common with actual Luddites. They seem more of a hippy movement than a “rage against the machine” one.

Thought-provoking Nicholas. There does seem to be a parallel, and even those of us dependent on some level of IT automation, are already feeling (acutely sometimes) the substitution of ‘virtual’ for real engagement.

How much worse it will be for those whose actual work is their immediate society!

We need leaders who can tackle this sort of challenge. I’m afraid we have the exact opposite.