You may remember Erik Kwakkel or Leiden University from earlier posts like A Fantasy Tip From History: Medieval Spam. Erik recently shared the incredible history of St. Albans Bible. I hope you enjoy it as much as I did!

A Horror Story

In 1964, the New York rare book dealer Philip Duschnes (d. 1970) bought and subsequently broke a splendid medieval Bible produced in early-fourteenth-century Paris.

Leaf from the St Albans Bible auctioned at Christie’s on 10 July 2019 (now part of the McCarthy Collection). Source

Every page is adorned with exuberant decoration, usually with gold leaf. With so much beauty on each page, to Duschnes the manuscript must have seemed ideal for breaking and selling by the leaf. In 1965, he began offering individual leaves for sale in his catalogue 169, stating that others from the same manuscript were available. Cut to order.

Yikes!

Breaking a book

St Albans Bible fragment at UBC, detail showing running title (Regu[m]). Source and zoom here

He bought this bible at the Sotheby’s auction of 6 July 1964 for £1,500 (approximately $12,000 today). At the time of purchase, the manuscript contained two flyleaves taken from a register from St Albans Abbey, which suggests a St Albans provenance. The abbey’s chronicle, moreover, detailed that abbot Michael de Mentmore (1335-1349) gifted two beautiful bibles to the community and Duschnes’s bible was believed to have been one of these two books. Following this assumption, auction catalogues have come to refer to the broken parent manuscript acquired by Duschnes as the “St Albans Bible,” despite the uncertainty surrounding its earliest provenance.

As a result of Duschnes’s dark deed, leaves from “the” St Albans Bible flooded the market and often found new homes in private collections (very few are held in university libraries). Even today, the book’s eye-catching leaves are frequently auctioned.

Auction houses do not usually identify new owners and, while leaves purchased by libraries may in time appear on the radar, especially when they are digitized, those in private collections may not be seen for many decades.

The origins of the St Albans Bible

Detail from the leaf from the St Albans Bible auctioned at Christie’s on 10 July 2019 (now part of the McCarthy Collection). Source

A thorough study of the St Albans Bible has yet to be conducted. This is likely due to the fact that the book was cut into pieces and scattered across multiple institutions and private owners.

In parallel to other Parisian products of this age, there are probably three artists at work in the manuscript.

One executed the historiated initials, a second the illumination (border decoration, chapter numbers, both made with gold leaf), while a third did the penwork flourishing. A forth individual copied the text.

The individuals involved in its production were affiliated to the famous Parisian illuminator and libraire (bookseller) Jean Pucelle.

The St Albans Bible was the product of a closely-knit community of artisans at the heart of the Parisian book trade. Those involved in the book’s creation lived and worked in the same street, which made it easy to get teams together.

The community brought together by Pucelle consisted of different artisans each time, although research shows that booksellers preferred to work with the same group of colleagues.

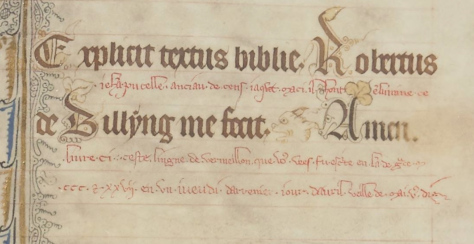

How do we know this? Because of an inscription at the end of the bible. In brown ink, it states:

Jean Pucelle, Anseau de Sens and Jacques Maci illuminated this book. This vermilion line that you see was written in the year of our Lord 1327, on a Thursday, the last day of April on the eve of May – this I tell you.

Colophon from 1327 identifying the scribe (“Robertus de Billyng me fecit”) and the three illuminators who worked on the book (Paris, BnF, latin 11935, fol. 642r). Source

You can read more about the history of St. Albans Bible on Medieval Books.

I have Erik Kwakkel’s Medieval Books to thank for this fascinating insight into the world of Medieval spam. Erik Kwakkel is a book historian and lecturer at Leiden University. His blog brings the world of medieval manuscripts to life in a wonderful way. You can read the original post in its entirety on his blog.

I have Erik Kwakkel’s Medieval Books to thank for this fascinating insight into the world of Medieval spam. Erik Kwakkel is a book historian and lecturer at Leiden University. His blog brings the world of medieval manuscripts to life in a wonderful way. You can read the original post in its entirety on his blog.

Fascinated that someone can sell each page! I once had a school assignment to create my own illuminated text page. Researching about the process was an enlightening endeavor.

It’s a fascinating process! I should blog about it one of these days.

What a disturbing history to the St. Albans bible. After viewing the Kells at the Trinity College in Dublin, it makes me ill to know someone could violate such a treasure that is part of our religious legacy.

Agreed! Even if you’re not religious, it’s still an affront to civilization.

Again the greed of humans is disgusting, what an atrocity to destroy such a treasure.

It saddens me to find out it’s, in fact, common practice.