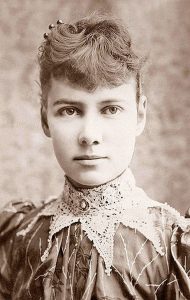

With all the controversy surrounding fake media and fake news, it’s easy to forget that real journalism not only has existed for a long time but has many forgotten heroes. One of them is Elizabeth Cochrane, a pioneering female journalist who’s finally getting her dues.

As The Washington Post reports, Nellie Bly, as Elizabeth’s pen name was, volunteered for an assignment so horrific that no one else had dared attempt: to infiltrate the notorious mental asylum on Blackwell’s Island and expose the abuses there. She had no guarantee she’d be able to leave and no way of entering except as an inmate.

Pulitzer’s Assignment

After working for the Pittsburgh Dispatch for a few years, Bly got her most dangerous assignment yet: to infiltrate the infamous asylum. Joseph Pulitzer himself gave it to her after she blustered her way into his offices and promised him she could deliver a major story. Impressed by her moxie, he asked her to go undercover at the asylum with no guidance even on how to gain entry, never mind how to get out.

Gaining Entry

In late September 1887, Bly threw herself into the role of a deranged woman to get committed. She practiced looking insane in front of a mirror with the idea that “far-away expressions have a crazy air,” as she wrote in her article. Then she checked herself into a working-class boardinghouse, hoping to frighten the other boarders so much that they would kick her out.

Using the name Nellie Brown, she pretended she was from Cuba and ranted that she was searching for “missing trunks.” Her ruse worked and the police were called. She had a hearing at a New York City court, where a judge ordered her to Blackwell’s Island, which at that time held a poorhouse, a smallpox hospital, a prison, and the insane asylum.

Blackwell’s Island

The horrid condition of the food in the mess hall was her first dose of deprivation.

Tea “tasted as if it had been made in copper,” she writes. Bread was spread with rancid butter. When she got a plain piece it was hard with a “dirty black color. . . . I found a spider in my slice so I did not eat it.” The oatmeal and molasses served at the meal was “wretched.” The next day she was served soup with one cold boiled potato and a chunk of beef, “which on investigation, proved to be slightly spoiled.”

To add to the torment, the building was freezing. “The draught went whizzing through the hall,” and “the patients looked blue with cold.” Within her first few days, she was forced to take an ice-cold bath in dirty water, sharing two “coarse” towels among 45 patients.

My teeth chattered and my limbs were goose-fleshed and blue with cold. Suddenly I got, one after the other, three buckets of water over my head — ice cold water, too — into my eyes, my ears, my nose and my mouth. I think I experienced the sensation of a drowning person as they dragged me, gasping, shivering and quaking, from the tub. For once I did look insane.

Despite the autumn chill, Bly and the other inmates were given threadbare dresses with poorly fitted undergarments after the frigid baths.

“Take a perfectly sane and healthy woman shut her up and make her sit from 6 a.m. to 8 p.m. on straight-back benches, do not allow her to talk or move during these hours . . . give her bad food and harsh treatment, and see how long it will take to make her insane. Two months would make her a mental and physical wreck.”

Bly made a point of talking to as many women as she could. Among the sane ones, she found that many were immigrants who didn’t understand English and seemed to have been mistakenly committed to the island. Others were just poor and thought they were going to a poorhouse, not an insane asylum, she wrote. All related horrible stories of neglect and heartless cruelty.

Mrs. Cotter, “a pretty, delicate woman,” told Bly that, “for crying, the nurses beat me with a broom-handle and jumped on me, injuring me internally, so that I shall never get over it.” She said the nurse then tied her hands and feet, threw a sheet over her head to muffle her screams and put her in a bathtub of cold water. “They held me under until I gave up every hope and became senseless.”

“The beatings I got there were something dreadful,” Bridget McGuinness told Bly. “I was pulled around by the hair, held under the water until I strangled, and I was choked and kicked. … It was hopeless to complain to the doctors, for they always said it was the imagination of our diseased brains, and besides we would get another beating for telling.”

Nurses drugged inmates with “so much morphine and chloral that the patients are made crazy,” Bly reported. “The attendants seemed to find amusement and pleasure in exciting the violent patients to do their worst,” she wrote.

Released

Exhausted and starving, Bly was relieved when, 10 days after her entry into the asylum, lawyers from the New York World arranged for her release. Though sorry to leave the suffering women, Bly was eager to write about what she had seen.

Two days later, on Oct. 9, 1887, the New York World printed the first part of Bly’s two-part illustrated series on the front page of the Sunday feature section. The blaring headlines of the second installment enticed readers: “Inside the Madhouse,” “Nelly Bly’s Experience in the Blackwell’s Island Asylum,” “How the City’s Unfortunate Wards are Fed and Treated,” “The Terrors of Cold Baths and Cruel, Unsympathetic Nurses.”

The Aftermath

Bly’s first-person account of abuse shocked the public. The story was so explosive that competing newspapers produced their own accounts of how Bly succeeded in her dangerous work, just to join in on the exposé.

Writers like Charles Dickens and Margaret Fuller had toured insane asylums and written about them. But those were guided tours and they didn’t see much.

Meanwhile, city officials began investigating the institution.

A month later, a grand jury panel went with Bly to visit the asylum. But it was too late. Inmates who told Bly of their treatment had been transferred or released. Buildings had been scrubbed down and patients had better food and water.

But despite the coverup, the grand jury believed what Bly had written. Shortly after the visit, officials added nearly $1 million to the asylum’s budget, an enormous amount for 1887.

Bly’s two-part series was released as a book two months later, called “Ten Days in a Mad-House.”

Having established her reputation as a “stunt girl” with a social justice bent, she went on to write exposés of baby-selling rackets and harsh conditions for factory workers. However, disgusted by the fact that Joseph Pulitzer barely acknowledged her feat, she quit the New York World.

Nellie Bly didn’t return to journalism until much later in her life, when she covered the eastern front during World War I. She died of pneumonia in 1922 at age 57.

A monument of Bly will now be placed on the very site of the asylum she wrote about.

Read the full post on this extraordinary woman on The Washington Post.

Wow! I had no idea. This was an interesting story and one can only imagine what it must have done to the inmates who were there long term.

I don’t even want to think about that…

A great story, Nicholas. She no doubt shortened her life getting those stories. She weakened herself. Few die today in their fifties from pneumonia. Some people are that dedicated. —- Suzanne

I hand’t thought of that, but you’re probably right!

Great story, Nicholas. That woman had what some would say ‘stones’!

You betcha!