Organized crime in New York is often portrayed as a boy’s game, but one of the first and most influential crime bosses in the history of the city was a Prussian immigrant known as “Mother” or “Marm” Mandelbaum.

Organized crime in New York is often portrayed as a boy’s game, but one of the first and most influential crime bosses in the history of the city was a Prussian immigrant known as “Mother” or “Marm” Mandelbaum.

Eric Grundhauser recently shared her fascinating story on Atlas Obscura, as did Sarah Breger in forward.com, based on Queen of Thieves: The True Story of “Marm” Mandelbaum and Her Gangs of New York” by J. North Conway.

The Queen of Fences

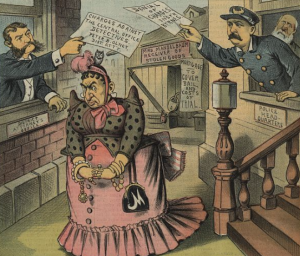

Marm (Fredericka) Mandelbaum, also called “The Queen of Fences,” was an imperious and powerful woman who became one of the most well-connected criminal figures of her day, buying stolen goods and reselling them, financing criminal endeavors, and even creating a school for young criminals.

Increasing restrictions against Jews in Germany brought Mandelbaum to the United States in 1850, with her husband Wolfe. They landed in New York, where they opened a general store. One of the interesting things is she remained fairly religious throughout her life. She settled in the German Jewish community and had very deep connections there. She was particularly attached to her synagogue—Rodeph Shalom in Queens.

In the beginning, Mandelbaum and her husband worked as flamboyant street peddlers, building relationships with both the hordes of aimless children and the petty thieves looking to get rid of their stolen loot. By 1865, Mandelbaum had opened a shop on Clinton Street to act as the front for her burgeoning criminal operation.

Like many criminals of the period, she had a duality in her life. She had her husband, family, religion, social events etc, and then she had the other side of her life. She remained devoted to Wolf and never remarried after he died. Wolfe loved to hear piano player and safe-cracker Charlie Bullard play. When Bullard was arrested, one of the reasons Fredericka broke him out of jail was to have him come back and play for an ailing Wolf.

Mandelbaum the Fence

Fencing stolen items became Mandelbaum’s main hustle. A criminal would steal anything from jewelry to furniture, and sell it to Mandelbaum, who would turn around and sell it to another buyer. Mandelbaum’s favorite items were bolts of silk and diamonds, both of which she could buy on the cheap and sell at a huge mark-up.

But she would take anything. Following the Great Chicago Fire, someone showed up at her haberdashery shop with a herd of goats they’d stolen during the fire, and she took them, says J. North Conway, author of Queen of Thieves: The True Story of “Marm” Mandelbaum and Her Gangs of New York. As Mandlebaum’s power grew, she branched out into financing bank robberies, and supporting all manner of criminal enterprise ranging from blackmail to theft to burglary.

Mandelbaum was six feet tall and said to be between 200-300 pounds, giving her an imposing physical presence. But it was her formidable network that allowed her criminal power to grow. She was known to fastidiously bribe and pay off police, local politicians, and judges, who allowed her operation to become a criminal ring worth millions.

Mandelbaum the teacher

Mandelbaum never got her hands dirty, instead building an inner circle of burglars, pickpockets, and robbers. To grow and support this network, Mandelbaum is said to have created a school that would train the many children living on the streets to be criminals. “The city was inundated at the time, with orphaned children. ‘Street rats,’ they called them,” says Conway. While no official transcripts of the curriculum seems to exist, Mandelbaum’s Grand Street School became maybe the first and most successful training center for crooks in the city.

The school was opened around 1870 behind a storefront on Clinton and Grand Street. Mandelbaum invited both young men and women to come and learn the criminal trades from professional thieves, pickpockets, and conmen. When young ne’er-do-wells enrolled in the school they started off learning about smaller crimes like pickpocketing and petty theft. They would be taught about things like misdirection and the finer points of thieving, then, if they had a knack for it, their training would advance. “If you were doing very well, you graduated up into other, more important things, which would include outright robberies and scams,” says Conway. Other higher level subjects included safe-cracking, blackmail, and burglary.

The star pupils would eventually move on to work directly for Mandelbaum. Her enterprise had a symbiotic relationship with the criminal community in that she needed a constant flow of thieves bringing her merchandise, and they needed a quick and reliable place to sell their ill-gotten gain.

One of Mandelbaum’s greatest students was Sophie Lyons, a master blackmailer and thief who, after working for Mandelbaum, went on to have her own impressive criminal career, becoming known as the “Princess of Crime.” Conway says that one of her scams involved luring men to a hotel room, letting them get naked, then stealing their clothes and extorting them for their cash to get them back.

In the early 20th century, however, Lyons reformed, denouncing her criminal career and her association with Mandelbaum’s training.

Whether or not Mandelbaum’s school was luring impressionable youth into a life of crime, her willingness to train and employ women in her crime ring created opportunities that were simply not available elsewhere. Despite the fact that it was in the arena of crime, Mandelbaum was credited with being one of the first feminists, because she was able to get women jobs in which they made more money and were able to use their skills in better ways than they did working in factories or as maids.

The Grand Street School operated for only about six years, closing down around 1876. Mandelbaum shut down the school when she found out that the son of a police official had enrolled. Rather than let this suspicious new student learn the ropes, risking her entire empire, she shuttered the school.

A glamorous end

Even after the closing of the school, Mandelbaum’s criminal empire continued to grow and thrive. In addition to the apartments above her Clinton Street shop where she conducted most of her business, Mandelbaum eventually had to keep two warehouses in the city to hold all of her dirty merchandise. With judges, policemen and politicians at her payroll, she was untouchable.

However, in 1884, there was a new district attorney, Peter Olney, who had vowed to clean up government. He pinpointed Mandelbaum as the nucleus of crime in New York City, but realized that he couldn’t trust anyone in government or police since they were likely on her payroll. So he bypassed them and brought in the private Pinkerton Detective Agency, who set up a sting operation. The Pinkertons tagged a bolt of silk, knowing her fondness for it. When it got stolen, she bought it, and at that point they closed in on her.

Mandelbaum had two of the best lawyers in the country but even they said they couldn’t get her off. She was released on bail for $30,000—which back in 1884 was a huge amount of money. Pinkerton detectives put her on 24-hour surveillance. One day they followed her to her lawyer’s office and then followed her back home. But it wasn’t her, it was one of her maids. She had literally slipped out the back door of her lawyer’s office with one million dollars in cash and diamonds. She went to Ontario, Canada, which at the time had no extradition treaty with the United States.

She only returned to the US once, in November 1885, when her daughter Annie died. Everyone—including The New York Times—knew she was there, yet she crossed the border untouched, even though those warrants were still open.

Mandelbaum died in 1894, while still living in criminal exile. Her body was returned to New York to be buried. Everybody turned out for her funeral— businessman, police and even a bunch of well-known criminals. But what was most ironic was the story that appeared in the Brooklyn Eagle the next day: After the graveside ceremony many attendees went to the police to report that they had been pickpocketed during the service.

Mandelbaum and her school may not have been on the right side of the law, but in her role empowering the women she trained and employed, she was on the right side of history.

What a story! Thanks for sharing 🙂

Thanks for enjoying it 🙂

Someone should write a fictionalised account of these ladies. It’s got mini-series written all over it. A school for criminals – I was going to make an obvious joke about government buildings, but it would be so much better if this got on TV instead…

Now, that’s a mini series I’d watch. Especially since the bad girl gets away with it!

brilliant, fascinating and precise approach,,,,

Thank you 🙂

Brilliant! I’d never heard of her but she cuts quite a figure!

A force to be reckoned with. Plus, she believed in both education and equal rights. You gotta admire that, right? 😀

Brilliant 🙂 I didn’t know about this particular crime boss but, believe it or not, one of the main characters in my most recently written novel has a Polish crime boss for a mother – a quite foul woman. Is the book about Mandalbaum light or heavy reading? What I mean is it dry and academic and likely to send me to sleep, or is it written for the less erudite reader?

I included it in case someone want to learn more about her, but I haven’t read it, actually. It’s in my tbr list. Sorry!

I just noticed the author got some terrible reviews, not because of the subject but because of his writing D: I’d seriously consider giving up writing if I had some review like that! Of course, sometimes people give bad reviews because they’re jealous that they didn’t think of the idea first!

Lol – only one way to find out! Check the excerpt 🙂

That scene at the gravesite must’ve been hilarious … what a great send-off. 😀

The perfect ending 😀

What a wonder. Fantastic woman who had the…um… guts to do as she pleased. 😀

😀 😀

Lol – yes, quite so 😀

A woman before her time, for sure!

I.n.d.e.e.d. 😀

What a character! Fascinating 😀

She does sound formidable!

Fascinating. Wow. She was a large woman, which I’m sure helped her in gaining the respect (driven by fear probably) of her underlings.

Very true. Size matters. I had you in mind when I posted this. I suspect you’ll also enjoy tomorrow’s post 🙂

I enjoyed this tale, especially how the mourners were pick-pocketed at her funeral!

Best wishes, Pete.

Lol – yes, that was the best part 😀