Marginalia. That is the official name for the edges of pages in medieval manuscripts. These are filled with anything from intriguingly detailed illustrations to random doodles. And they are far more important than you may realize, as both tell us huge amounts about a book’s history and the people who have contributed to it, from its creation to the present day. As for me, they are a great source of fascination, especially when they depict killer bunnies.

Marginalia’s Medical Uses

As Anika Burgess of Atlas Obscura explains, on medieval pages, marginalia can run from the decorative to the downright bizarre. There are two broad categories of marginalia: illustrations intended to accompany the text and later annotations by owners and readers. Both can be vehicles for delight, disgust, and befuddlement.

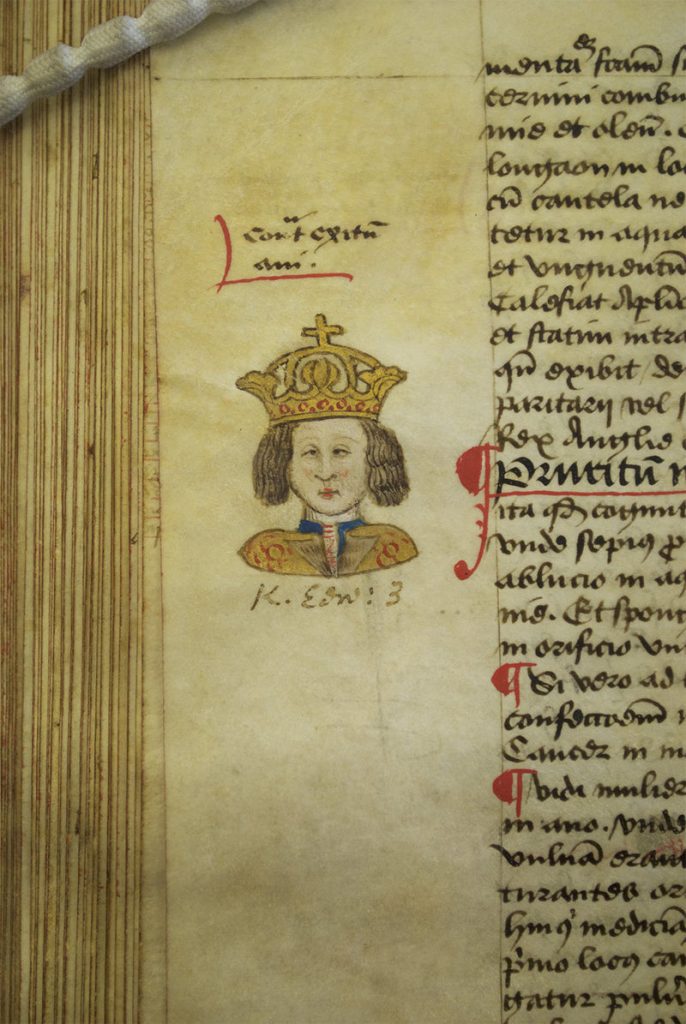

An example of useful intentional illustrations can be found in John of Arderne’s Mirror of Phlebotomy & Practice of Surgery, which is located at the Glasgow University Library. Known as the “Father of English Surgery,” Arderne produced several important medical texts in the 14th century. Fortunately, he was also a prodigious illustrator. His textbooks contain ample amounts of delightfully detailed (and occasionally rather gruesome) illustrations. Take for example the following painful-looking medical procedure:

The margins are full of images of disembodied body parts, plants, animals, even portraits of cross-eyed kings, which relate to the main body of text and act as a mnemonic for the reader.

Illustrations from John of Arderne’s medical treatise Mirror of Phlebotomy & Practice of Surgery. Image via Atlas Obscura

Mercifully, not all marginalia are quite as gruesome.

Artistic Marginalia

In Arderne’s texts the marginalia has a clear purpose, but in other manuscripts, the meaning of the drawings can be indecipherable. There are countless examples of unusual marginalia—monkeys playing the bagpipes, centaurs, knights in combat with snails, naked bishops, and strange human-animal hybrids that seem to defy categorization. And some are plainly done for fun: art for the sake of art.

Doodling Away

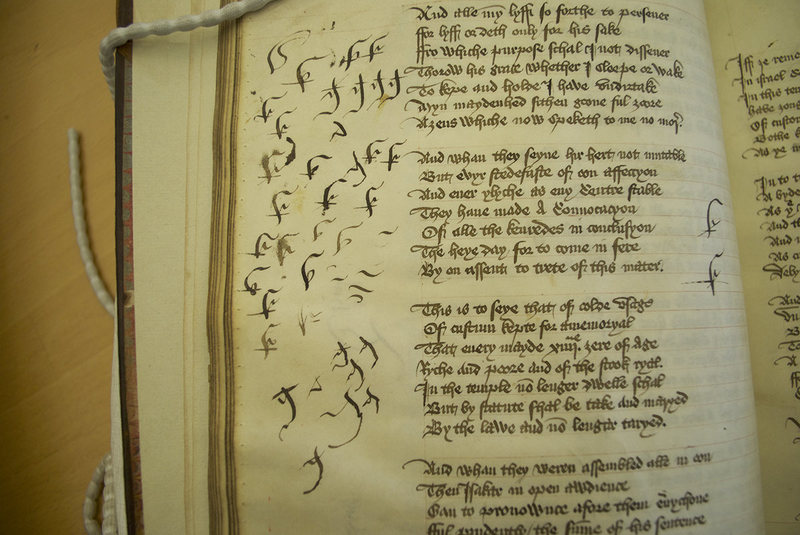

Finally, there are examples of marginalia that are simple doodles. Even though it sounds sacrilegious to doodle away on the margins of priceless books, this is exactly what people have been doing for centuries. Fret not, though. Each such doodle gives us an insight into the kinds of encounters or interactions those people had with these books. For medieval texts, a gloss, biblical reference, or some commentary suggests the user was reading the text closely, compared with pen trials which show scribes breaking in a new nib, while other marks and illustrations often give the impression of a bored reader using the blank parchment of the book as we might use scrap paper. It is essentially a form of archaeology, but for books. Check out, for example, the pen trials of various letters below:

And some are obviously just kids doing what kids do best: happily destroying their parent’s books.

The Highlighter, aka The Manicule

An elaborate manicule that forms part of the illustration, pointing towards the Virgin Mary and Jesus. The Latin words Ecce Ancilla Domini translate to “Behold the handmaid of the Lord.” Image via Atlas Obscura

Last but not least, there is a kind of ubiquitous annotation that deserves its own category: tiny hands serving as highlighters, aka manicules. The Manicule is a pointedly unique symbol. Quite literally: it takes the form of a hand with an outstretched index figure, gesturing towards a particularly pertinent piece of text. Although manicules are still visible today in old signage and retro décor, their heyday was in medieval and Renaissance Europe.

Despite its centuries-long popularity, the first-ever use of a manicule is surprisingly difficult to pinpoint. They were reportedly used in the Domesday Book of 1066, a record of land ownership in England and Wales, but widespread use began around the 12th century. The name comes from the Latin word manicula—little hand—but the punctuation mark has had other synonyms, including bishop’s fist, pointing hand, digit, and fist.

As far as punctuation marks go, the manicule’s function was fairly self-explanatory. Usually drawn in the margin of a page (and sometimes between columns of text or sentences), it was a way for the reader to note a particularly significant paragraph of text. They were essentially the medieval version of a highlighter. Although mainly used by readers, a scribe or a printer would occasionally draw a manicule to indicate a new section in a book.

The Manicule’s Descendents

The use and dynamic of manicules changed once books began to be printed. This new technology allowed writers and publishers to highlight what they believed to be significant. The margin, once the reader’s workspace and sketchbook, was gradually colonized by writers seeking to provide their own explanatory notes or commentaries.

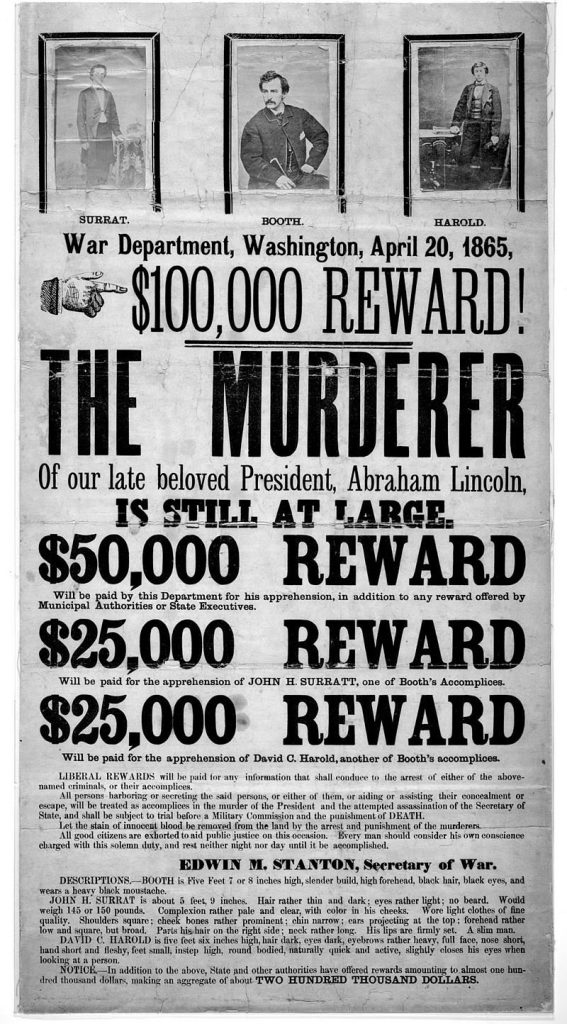

In the 19th century, manicules had moved beyond books and into signage, advertisements, and posters as a way of directing the eye. They pointed the way to trains and pubs. In the “Wanted” poster for John Wilkes Booth following his assassination of President Lincoln, a manicule gestured towards the reward announcement. Manicules were even used on gravestones (pointing up toward heaven, of course).

You can see more example of and manicules and marginalia on Atlas Obscura, including a disembodied penis, a man riding a peacock, and (yay!) more vengeful rabbits.

Still hunting, pondering and enjoying my project of HARES AND SNAILS keep on supplying such great thoughts and material Nicholas. Thanks

As a fellow Medieval-books-and-hares-enthusiast, I thank you 🙂

If it appears in the Life of the Virgin, perhaps the ship was a prayer, like the doodles on church walls you posted about a while back. 🙂

Lol – yes, that must be it 😀

I love this kind of stuff. I literally went crazy when I saw some of the original illuminated manuscripts on my last trip to Italy. Great article.

Yay! Thank you 😀

I wait for these posts on the history of manuscripts, and you never disappoint. Thank you for so many stunning visuals.

Thank you so much Veronica–I’m glad to see I’m not the only one who loves this kind of posts 😀

It’s fascinating, funny, weird, and in some cases, beautiful. Great post, Nicholas. 🙂

Thank you so much, D! I love preparing these “weird history” posts 🙂

A great piece explaining things that we knew there must be a word for but never thought to ask

Thanks! “Things we knew there must be a word for but never thought to ask” would be a great title for a post 😀

Wonderful stuff, Nicholas. A joy to read indeed.

Best wishes, Pete.

Thank you so much, Pete! These posts are so much fun to prepare 🙂

An informative and humorous post, Nicholas. Thanks for sharing. 🙂 — Suzanne

Thank you so much, Suzanne 🙂

A wonderful, fun post, as usual!

Thank you! I do love preparing these “weird history” posts 🙂